A New Hope House

Fifty miles from Atlanta isn’t far for fans of “Stranger Things” on their pilgrimage to Jackson, Ga., where the hit series is filmed. The Highway 36 exit off Interstate 75 takes you straight into town, right past the Georgia Diagnostic and Classification Prison, home to the most threatening reality in Georgia — the state’s death row. For the families of the 37 men inside during 2022, Jackson can seem impossible to reach. COVID-19 restrictions made it even harder to follow Jesus’ admonition in Matthew 25 to ‘visit the prisoners.’

One aging solution had been a creaky 2006 minivan nicknamed “Golden Girl,” and driven more than 300,000 miles by New Hope House, a Christian ministry to death row families in Georgia. “I was praying that it would make it, especially because some of the death penalty trials are in places like Eatonton where you have to drive on backroads with no cell service,” said Mary Catherine Johnson, the organization’s executive director who is usually behind the wheel. At a pre-execution vigil in Jackson, she mentioned her transportation need to one of her board members, Bishop Rob Wright.

In 2022, a much needed new replacement sprung forth: a 2022 hybrid Toyota Sienna van with plenty of room for care packages and passengers headed to visit their loved ones on death row. The van was funded through grants from St. Bartholomew’s Episcopal Church in Atlanta and the Episcopal Community Foundation for Middle and North Georgia. “Transportation on Justice Road just got kicked up a notch!” Johnson exulted.

A sturdy vehicle is key for easing the isolation of families and incarcerated people that are separated across Georgia’s 59,425 square miles.

“Until you go through it, you can’t imagine living like this,” said Deborah Morrow, who got a few rides from Athens in the old van to visit her brother Scotty Morrow before he was executed in 2019. Morrow relies on disability assistance, and when funds were tight, she couldn’t afford the gas to drive to Jackson. The van rides are proof that New Hope House is “a guardian angel for me,” she says. And that angel was more than a chauffeur.

Visitors to death row are not allowed to take anything into the prison except quarters for the vending machines in the visitation rooms, and New Hope House provides each visitor $20 in quarters. The snacks and drinks are a special treat for the prisoners. “We affectionately call this the vending machine Eucharist,” Johnson said.

When the extended Morrow family traveled to Atlanta to testify in a clemency hearing in 2018, New Hope House provided their housing, meals, and transportation. The no-strings assistance has helped Morrow recover from her own trauma related to her brother’s crime.

“Even though he was in custody, we feared for our lives because of the anger that people had toward us,” she said. Tension was so high during her brother’s capital trial in Gainesville that police escorted her family in and out of the courthouse.

Families of death row incarcerated people “are lumped in with the offender and sometimes blamed and shamed,” said Susan Casey, an Atlanta attorney who began representing defendants in capital cases in 2000. She is a member of St. Bartholomew’s and serves on the New Hope House board. “The greatest gift that we human beings can give each other is comfort to people who are in really personal pain that’s on public view.”

The Men on Death Row

According to the state’s incarcerated person statistical profile for September 2022, the 37 men on Death Row in Jackson have a median age of 50, and median age at sentencing of 28. (Georgia’s one woman on death row is housed at Lee Arrendale State Prison in the north Georgia town of Alto). There are 18 Black men, 17 white and 2 Hispanic. Of the 31 who reported a religious affiliation, 26 are Protestant or Catholic. There are 24 incarcerated people who have served more than a decade.

The men came to this prison from Glynn County on the coast to Floyd County in northeast Georgia to Muscogee on the Alabama border. The largest number come from metro Atlanta. In a typical year, the van travels 18,000 miles crisscrossing the state, serving their families.

In the isolation and stigma of death row, the smallest gesture of kindness takes on greater significance. Larry Lee, who was exonerated after more than 20 years on death row, described the public hostility and his gratitude for the care packages, partially funded by St. Bartholomew’s, that New Hope House delivers each Christmas.

“I felt like the world hated me, and here would come these packages from people that I didn’t even know,” Lee wrote to a penpal arranged through New Hope House. “It gave me hope more than anything that maybe I wasn’t as hated as I imagined, that there were people out there who actually cared… for me it was so much more than the good things to eat! It was the love that came with them.”

I Care For You

The new van is symbolic of local Episcopalian advocacy to end the death penalty and the longtime dedication of volunteers like Neva Corbin at St. Bartholomew’s. She and other parishioners secured a grant of $10,370 for the van and other expenses. Corbin joined the Episcopal Church partly for its unequivocal stance against the death penalty.

“It was just so unjust. It was just so distasteful to have people parked on death row,” she said. “There’s no hope and they stay there year after year after year, and they are people who didn’t have family, who didn’t have support, who didn’t have just the basic message, ‘I care for you.’

A retired writing instructor and government trainer, Corbin’s first main step as a volunteer was to write letters to a death row incarcerated person. Eight years later, she leads a core group of about 40 volunteers who attend execution vigils and lobby their state legislators to end the death penalty, and for greater justice and mercy for those incarcerated.

The work “has opened our eyes about the power of God’s grace and redemption,” Corbin said. “One parishioner shared that her involvement with death row prisoners has not always been an easy growth, but ‘we have a better sense of the inequality and brutality of the prison system. I think that stretches us spiritually.’”

45 Years of Lawful Executions in Georgia

New Hope House grew in response to the increase in death row incarcerated people after the U.S. Supreme Court reinstated the death penalty in 1976, ruling that a convicted Georgia murderer Troy Leon Gregg could be executed. In 1988, three Christian activist groups in Georgia (Open Door Community, Koinonia Farm and Jubilee Partners) opened New Hope House as a sanctuary for families to gather before and after visiting hours on death row.

Volunteers were soon on the road to death penalty trials, because one defendant’s mom had mentioned the comfort of sitting with someone who didn’t want her son to be put to death.

A ministry of presence was born in county courtrooms. Otherwise, “a lot of times they’re sitting there alone and the other side of the courtroom is stacked with all the victim’s families and police,” said Johnson, who began volunteering in 2008. “It’s a very intimidating situation.”

Most courtrooms have an aisle down the center that Sister Helen Prejean, the noted anti-death penalty activist, compared to the vertical part of Jesus’ cross. “Imagine the body of Jesus on that crucifix, and each one of his arms is reaching out to each side of the courtroom equally,” Johnson said. “Jesus isn’t taking sides, and we all meet in the heart of Jesus.”

Sometimes family members need a ride in the van to buy themselves essentials. The week before her son’s 2019 execution, one death row mother “arrived in sweats, and she wanted to look nice for the parole board when she was begging them to spare her son’s life,” Johnson said. “We went out to get her a dress and her hair done. She wore that outfit to the parole board and to her son’s funeral.”

Amid the isolation of the men on death row and the trauma of their families, the van helps make possible simple, meaningful acts of service. One prisoner asked Johnson to drive to his family church and cemetery, and “he was so happy to have pictures of the places that connect him to his loved ones,” she said. “I also drove to a hearing in Madison to support the legal team of another man I visit on death row, and am planning to attend several more hearings and death penalty trials in the coming months. I was also able to use episcopal funding to load the van with art supplies, books, and puzzles for all of the men on death row to share.” Sometimes making a way in the wilderness depends on a new minivan.

Further Reading

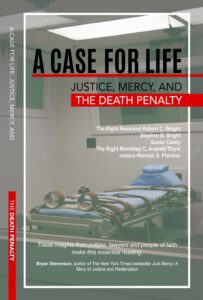

The five authors of this book make compelling arguments against the death penalty from their perspectives as lawyers, a supreme court justice and faith leaders. Their experiences with both victims and perpetrators also provide a moral case for ending state-sponsored killing.

Listen In

In this episode, Bishop Wright has a conversation with Sister Helen Prejean, a Roman Catholic nun and a leading American advocate for the abolition of the death penalty.